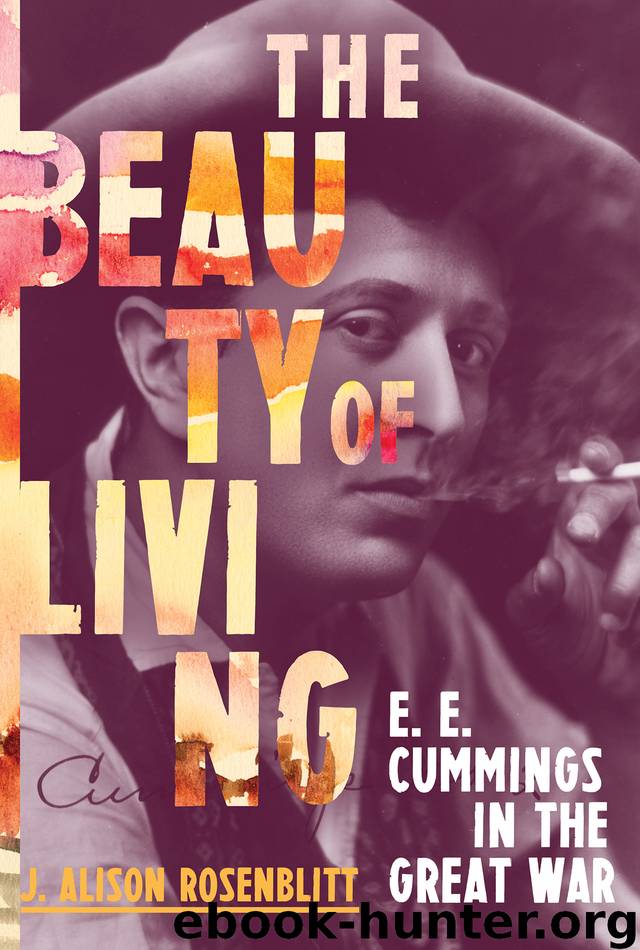

The Beauty of Living by J. Alison Rosenblitt

Author:J. Alison Rosenblitt

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Published: 2020-04-27T16:00:00+00:00

20

TIME STANDS STILL

In prison, time stood still. “It is like a vast grey box in which are laid helter-skelter a great many toys,each of which is itself completely significant apart from the always unchanging temporal dimension which merely contains it along with the rest. I make this point clear for the benefit of any of my readers who have not had the distinguished privilege of being in jail.” To speculate about release was to risk insanity.

Cummings fought hard to stay sane. The loss of any sense of time was not merely a literary conceit. He could not remember when he met with a new panel of interrogators—a commission charged with hearing his case and putting forward a recommendation either for permanent detention or for release. In The Enormous Room, he dates the commission to late November, but external documents prove that it met on October 17. The three commissioners came to La Ferté to hear cases. Neither Cummings nor Brown was informed of the outcome of their hearing. So they waited.

He discharged his anger into his notebooks. One of the La Ferté notebooks opens to a spread of notes on the child, religion, art, life, and death. At the top is written:

Man is the inconsiderable excrement

Life of ages

His notes on religion suggest that religion gives scope to the “intellectual expression of revenge” in the shape of hell. Ditto the intellectual expression of envy. Religion therefore grows from the idea of punishment.

He rejected the intellect and embraced feeling. Fear is intellectual. Anger is intellectual. Any real community of spirit has to be built on shared feeling; shared discourse does not facilitate peace but in fact prevents it. He penned a note/query to self: “Since War is purely Thoughtful, no 2 nations speaking same language (= directing ideas) can make allies (?).” Or to put it another way, through an interchange with a Mexican national also imprisoned at La Ferté: “When we asked him once what he thought about the war,he replied ‘I t’ink lotta bullshit’ which,upon copious reflection,I decided absolutely expressed my own point of view.” In one of the few letters that escaped the prison censors at La Ferté, Cummings wrote to Scofield Thayer: “How intellectual is war: a millimeter turn of a round-screw, x jumps high in the midst of his merriment over y’s uncouth hop.” It was his sarcastic way of referring to the technological advancements that allowed the turn of a screw to bring the “uncouth hop” of death as mud and men are blasted into the air.

The idea of war as a crime of thought against feeling made its way into his published poetry. His first solo collection of poems, Tulips & Chimneys (1922 ms), was divided into two sections, the first of which is the “Tulips,” and the second, the “Chimneys” of the volume’s title. The “Chimneys” section contains only sonnets, one of which begins:

when my sensational moments are no more

unjoyously bullied of vilest mind

and sweet uncaring earth by thoughtful war

heaped wholly with high wilt of human rind—

Cummings expects his reader to disentangle a kind of root meaning in his language.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African | Asian |

| Australian & Oceanian | Canadian |

| Caribbean & Latin American | European |

| Jewish | Middle Eastern |

| Russian | United States |

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(11046)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(6852)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(5877)

Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear by Elizabeth Gilbert(4723)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(4574)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4213)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(3991)

Ken Follett - World without end by Ken Follett(3972)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(3799)

Bluets by Maggie Nelson(3709)

Adulting by Kelly Williams Brown(3668)

Guilty Pleasures by Laurell K Hamilton(3586)

Eat That Frog! by Brian Tracy(3513)

White Noise - A Novel by Don DeLillo(3434)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(3366)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(3310)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3225)

The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama(3217)

Fingerprints of the Gods by Graham Hancock(3211)