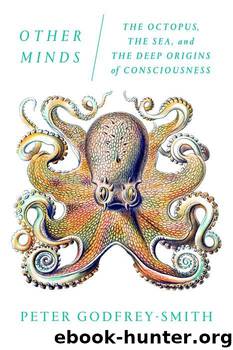

Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness by Peter Godfrey-Smith

Author:Peter Godfrey-Smith

Language: eng

Format: mobi, azw3

Tags: Science, Philosophy, Psychology

ISBN: 0374227764

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Published: 2016-12-06T08:00:00+00:00

6

OUR MINDS AND OTHERS

From Hume to Vygotsky

In one of the most famous passages in all of philosophy, David Hume in 1739 looked inside his mind in an attempt to find his self. He tried to find some enduring presence, a permanent and stable being which persists through the jumbled flow of experience. He claimed he could find no such thing. All he could find was a rapid succession of images, momentary passions, and so on. “I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of heat or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure. I never can catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe any thing but the perception.” These sensations or perceptions, he said, comprise him—nothing more. A person is just a bundle or collection of images and feelings, “which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and movement.”

Hume’s look inside provides a good starting point for this chapter because everyone can do what he did. When we do, despite Hume’s confident inventory, we surely find two things that he did not mention. First, Hume described what he found inside as a “succession” of sensations. But it seems more accurate to say that we find a combination of sensations present at each time. Our experience usually forms an integrated “scene”—a mix of visual information, sounds, a sense of where our body is, and so on. It’s not one impression after another, but several at each time, tied together. As time moves forward, one such combination passes into another.

The second thing Hume missed is more conspicuous. When we look inside, most people find a flow of inner speech, a monologue that accompanies much of our conscious life. Sentences and phrases, exclamations, rambling commentaries, speeches we would like to give, or wish we’d given. Maybe Hume did not find this in his own case? Some people have a more prominent inner monologue than others. Perhaps Hume was one of those for whom inner speech is weak? It’s possible, but I think it’s more likely that Hume did encounter inner speech, but regarded it as one part of the wash of sensations, not as anything special. There are colors and shapes and emotions in there, and echoes of speech as well.

Hume’s inattention to inner speech may also have been guided by his overall agenda in philosophy, by the shape of the theory he wanted to defend. Hume was inspired by Isaac Newton’s theories in physics, unleashed about fifty years before. Newton saw the world as made up of tiny objects ruled by laws of motion and a principle of attraction between them, also known as gravity. Hume aimed at an explanation of the same kind of the contents of the mind, and thought that he had discovered a “power of attraction” between sensory impressions and ideas, a complement to Newton’s attraction between physical objects. Hume wanted a science of the mind that took the form of a quasi-physics, in which ideas would behave like mental atoms.

Download

Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness by Peter Godfrey-Smith.azw3

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4111)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(3750)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(3506)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3227)

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid(3173)

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything by David Christian(3133)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(2944)

How to Read Water: Clues and Patterns from Puddles to the Sea (Natural Navigation) by Tristan Gooley(2849)

Hedgerow by John Wright(2771)

The Inner Life of Animals by Peter Wohlleben(2763)

Origin Story by David Christian(2677)

How to Read Nature by Tristan Gooley(2657)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(2654)

How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell(2640)

A Forest Journey by John Perlin(2583)

Water by Ian Miller(2579)

The Plant Messiah by Carlos Magdalena(2451)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2358)

Forests: A Very Short Introduction by Jaboury Ghazoul(2331)