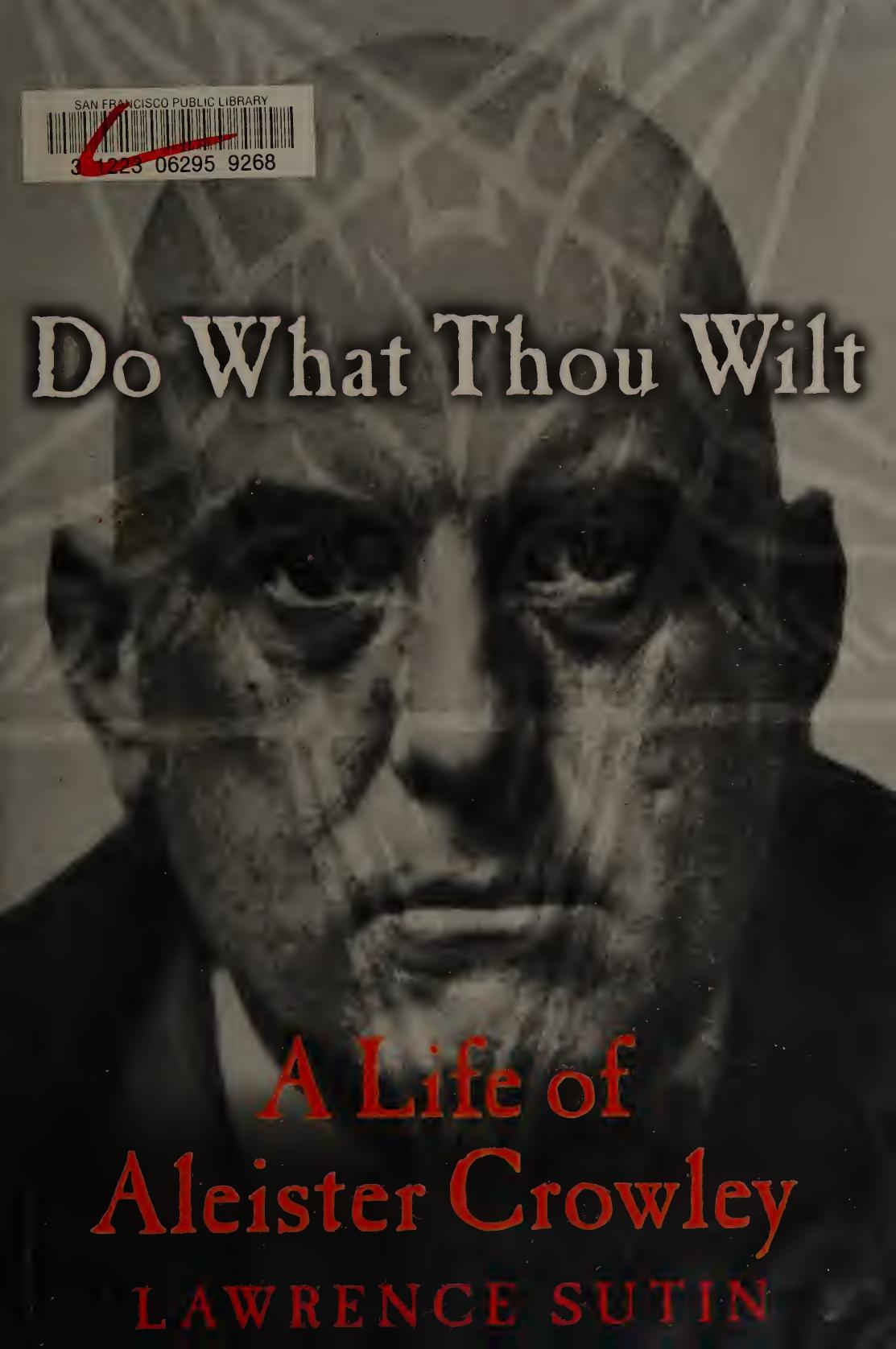

Do What Thou Wilt: A Life of Aleister Crowley by Lawrence Sutin

Author:Lawrence Sutin

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub, pdf

ISBN: 9781466875265

Publisher: St. Martin's Press

Published: 2014-07-08T00:00:00+00:00

CHAPTER SEVEN

In Exile in America, Crowley Endures Poverty and Accusations of Treason as Ordeals Necessary to Becoming a Magus (1914â19)

Upon arrival in New York in late October 1914, Crowley was already something of a celebrity, thanks to a lurid account of his London doings which preceded his arrival.

The account appeared in the August 2, 1914, The World Magazine, a publication of the New York World newspaper. The author was Harry Kemp, an American poet whose reputation has since gone into eclipse, but who was at the time a renowned bohemian. Kemp limned a portrait of forbidden practices at Crowleyâs Fulham Road studio in London:

One by one the worshippers entered. They were mostly women of aristrocratic type.[ ⦠] It was whispered to me that not a few people of noble descent belonged to the Satanists.[ ⦠] Then came the slow, monotonous chant of the high priest: âThere is no good. Evil is good. Blessed be the Principle of Evil. All hail, Prince of the World, to whom even God Himself has given dominion.â A sound as of evil bleating filled the pauses of these blasphemous utterances.

Kemp privately acknowledged that the piece was âa turgid bit of sensational journalism.â Crowley termed it ârubbish.â The World Magazine ran a subsequent piece on Crowley (by a different reporter) in its December 13, 1914, issue. Crowley was now describedâwith admirable accuracyâas âa man about whom men quarrel. Intensely magnetic, he attracts people or repels them with equal violence. His personality seems to breed rumors. Everywhere they follow him.â Crowley answered back at Kemp, declaring that he had made Kemp âdream a scene of black magic, and he thought it was actually happening and that I was participating. I donât practice black magic.â

Shortly after his arrival, Crowley met with John Quinn, the wealthy lawyer and arts patron to whom Crowley hoped to sell some of his own limited editions. He further desired to win over Quinn as an ally, as Quinn was influential in intellectual circles both in America and in England, and in correspondence with the leading figures of literary modernism, including Pound, Yeats, and (a few years later) James Joyce. But by late February, Quinn resolved to sever relations. As he wrote to Yeats (who had crossed swords with Crowley in 1900): âFrankly, his âmagicâ and astrology bored me beyond words. Whatever he may be, he has no personality. I am not interested in his morals or lack of morals. He may or may not be a good or profound or crooked student or practitioner of magic. To me, he is only a third- or fourth-rate poet.â

This rejection by Quinn effectively ended Crowleyâs chances of forming sympathetic social ties with the modernist movementâfor which Crowley, a poetic traditionalist, would always express a visceral contempt. In turn, Crowley was anathema to Pound, Yeats, and their circle. Thus in 1917, Pound, writing from London to the influential American quarterly The Little Review, objected strongly to the presence of a favorable footnote on Crowley in an essay by H.

Download

Do What Thou Wilt: A Life of Aleister Crowley by Lawrence Sutin.epub

Do What Thou Wilt: A Life of Aleister Crowley by Lawrence Sutin.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Becoming Supernatural by Dr. Joe Dispenza(7105)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(6946)

The Witchcraft of Salem Village by Shirley Jackson(6584)

Inner Engineering: A Yogi's Guide to Joy by Sadhguru(5895)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(5511)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(4755)

The Wisdom of Sundays by Oprah Winfrey(4626)

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(4107)

Fear by Osho(4085)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4001)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(3881)

Rising Strong by Brene Brown(3780)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(3755)

How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan(3676)

Sigil Witchery by Laura Tempest Zakroff(3651)

Real Magic by Dean Radin PhD(3568)

Secrets of Antigravity Propulsion: Tesla, UFOs, and Classified Aerospace Technology by Ph.D. Paul A. Laviolette(3448)

The Art of Happiness by The Dalai Lama(3384)

Man and His Symbols by Carl Gustav Jung(3315)