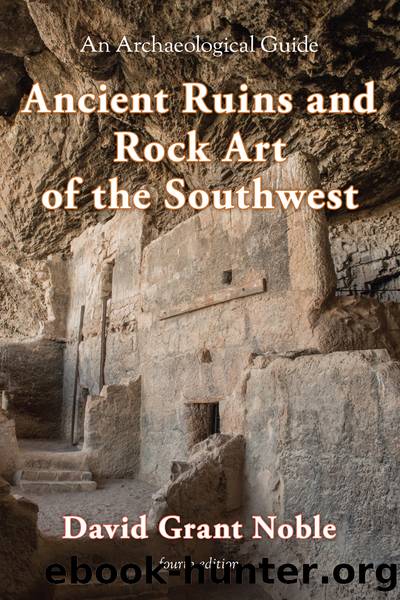

Ancient Ruins and Rock Art of the Southwest by David Grant Noble

Author:David Grant Noble

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781589799387

Publisher: Taylor Trade Publishing

View of Chaco Canyon from Hungo Pavi, looking toward Fajada Butte.

So what does all this mean? For more than a century, this question has been at the root of all discussions about Chaco. A currently prevailing theory holds that families of an elite class lived in the north-side great houses while the small houses were lived in by common folk. Chaco Canyon, as the architecture alone demonstrates, was a place of differentiated socioeconomic classes: some rich and powerful families, and working-class folk. Clues in the archaeological record have led to differing interpretations of the makeup of Chacoâs society; thus, many papers, books, and debates. As you walk around the ruins, consider possible parallels you are familiar with in the modern world and you may come to your own conclusions.

Chaco Canyon received most of its resourcesâwood construction timbers, pottery, grinding stones, some corn, and special goods such as macaw feathers, copper bells, and chocolateâfrom elsewhere. To obtain these goods, what did Chaco exchange? This is a puzzle. Some scholars, however, think they traded something of a nonmaterial nature, such as religious rituals performed by priests in the great houses to bring harmony and balance in the worldâand rain. Indeed, Chaco may have been a religious center to which people from the region came periodically to participate in ceremonies that were necessary to attain the favor of the spirit beings who send moisture and fertility and make it possible to survive in a challenging environment.

Archaeological research began here in May 1877 when William Henry Jackson mapped the major ruins. In the late 1890s, the Hyde Exploring Expedition carried out excavations in Pueblo Bonito. Since then, institutions that have sponsored research in the canyon have included the University of New Mexico, the National Geographic Society, the Smithsonian, and the National Park Service. Much data are held in archives.

Archaeologists have recorded as many as two hundred buildings beyond Chaco Canyon that resemble, though on a smaller scale, the great houses of the canyon. These outlying Chaco great houses, often referred to as âoutliers,â can be found from a few miles to well over a hundred miles away. Clearly, Chacoâs influence, particularly between 1050 and 1140, spread far and wide. Exactly what the relationship was between the far-flung outliers and Chaco central is a focus of ongoing investigation.

Another subject of research is the so-called Chaco roads, of which the North Road and the South Road are the best known. These two reach out from the canyon for many miles and are 30 feet wide in places. Some roads had formal borders and climbed over mesas by means of ramps and stairs. Most, however, extended only a short distance from outlying great-house complexes. It is speculated that they were used for ceremonial processions, perhaps not unlike those that occur around Roman Catholic churches and cathedrals during religious holidays.

Around 1140 CE, during a drought, the Chaco phenomenon ceased. Most Chaco Canyon residents left, and the great houses began the slow process of crumbling to mounds. The exodus appears to have been methodical, not motivated by warfare.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Never by Ken Follett(2872)

The Man Who Died Twice by Richard Osman(2289)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(2264)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(2058)

Will by Will Smith(2032)

Rationality by Steven Pinker(1760)

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber & David Wengrow(1564)

The Dark Hours by Michael Connelly(1562)

Principles for Dealing With the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed and Fail by Ray Dalio(1368)

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing by Matthew Perry(1321)

A Short History of War by Jeremy Black(1295)

HBR's 10 Must Reads 2022 by Harvard Business Review(1251)

Go Tell the Bees That I Am Gone by Diana Gabaldon(1231)

Can't Hurt Me: Master Your Mind and Defy the Odds - Clean Edition by David Goggins(1218)

515945210 by Unknown(1205)

Fear No Evil by James Patterson(1106)

443319537 by Unknown(1069)

Works by Richard Wright(1017)

Going There by Katie Couric(988)