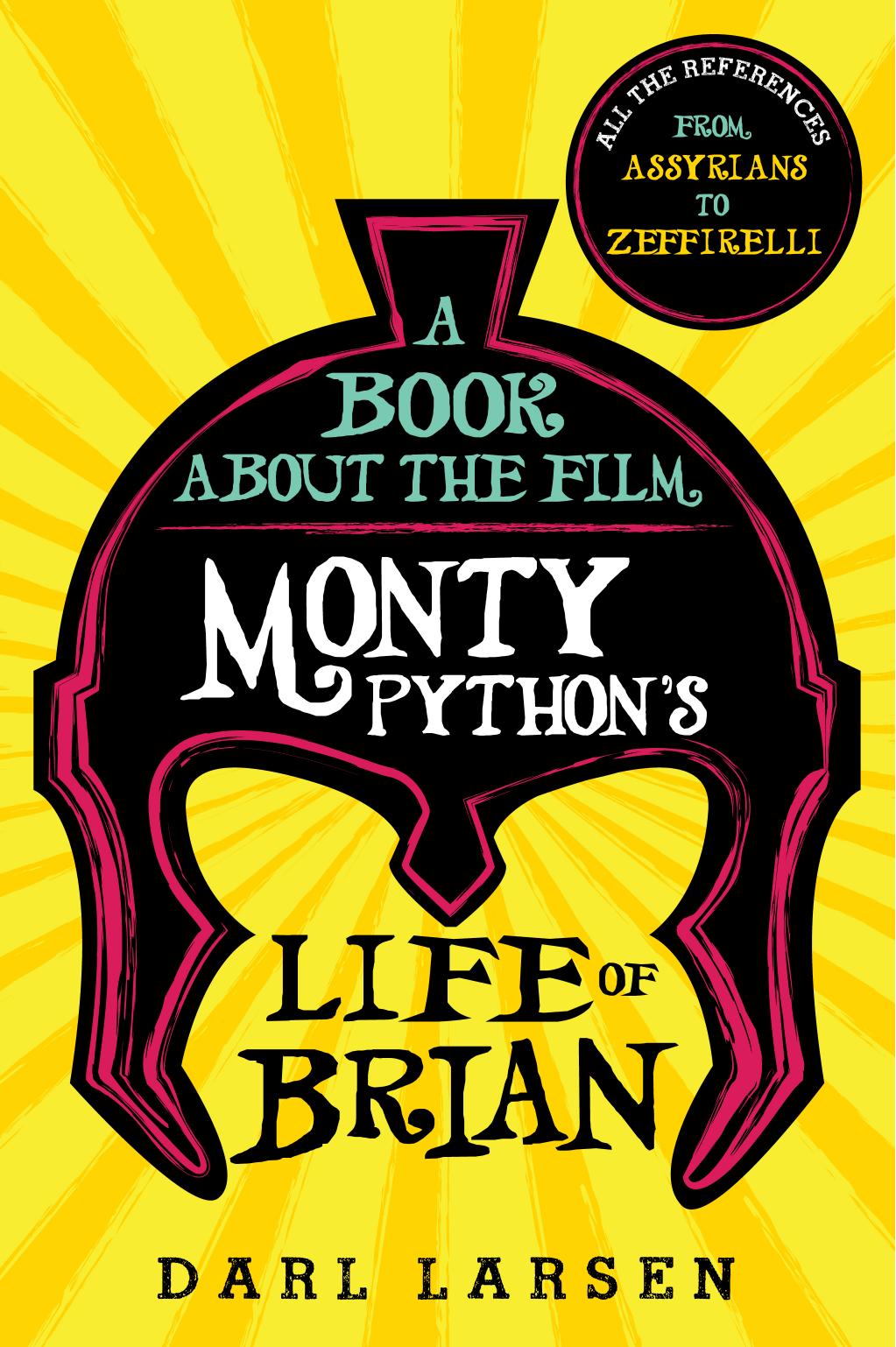

A Book about the Film Monty Python's Life of Brian by Darl Larsen

Author:Darl Larsen [Larsen, Darl]

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Publisher: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

Published: 2017-11-28T05:00:00+00:00

Scene Eleven

In the Palace Sewers

(draft) . . . eight MASKED COMMANDOS. Their faces are partially hidden—Even though this film is carefully crafted to reflect the look and atmosphere of first-century Judea (just like Holy Grail displayed a tenth-to-fourteenth-century mien), the connections between the “then” and the “now” are detectable, perhaps most initially and most identifiably in visual forms. The commando attire in this scene reflects not only the sicarii religious/terrorist sect, but the very recent and harrowing images of balaclava-wearing terrorists leaning out of hijacked airliners in the Jordanian desert1 or peering over balconies of the athletes’ village at the Munich Olympics. Our “masked commandos” are at least partially based on the notorious sicarii terror group, whom Laqueur describes as “a highly organized religious sect consisting of men of lower orders active in the Zealot struggle in Palestine.”2 What differentiates these men from the Zealots of the first century is that the Zealots were “primarily a coalition of peasants turned brigands [who] first challenged and then successfully opposed the high priestly regime in Jerusalem.”3 The PFJ are fighting the Romans, period.

Incidentally, the term “commando” is relatively young, harking back to the activities of the Boers across South Africa, where “commandos” were armed, civilian-led raids into native territories to recover stolen cattle, goods, and kidnapped women and children.4 By the mid-1970s, commando missions were more military in nature—heavily armed military units inserted into inimical and (often) postcolonial territory to “rescue the innocent from the consequences of terrorism.”5 The West German military snuck into Mogadishu in October 1977 to save hostages taken by the PFLP from Lufthansa Flight 181; this less than a year after the Israeli commando raid at Entebbe—which set the example for action for many governments’ future responses to terrorism—had saved more than one hundred hostages from Air France Flight 139.6 The Entebbe raid had spawned not only worldwide news coverage but three separate films from which the Pythons could draw influence: Victory at Entebbe and Raid on Entebbe, both 1976, and Operation Thunderbolt, 1977. Victory began life as an ABC television movie; Raid was a Hollywood feature film for cinemas; and Thunderbolt was an Israeli-influenced production helmed by Menahem Golan, with appearances from some of the actual participants in the raid. Times critic David Robinson reviewed both Raid and Victory in the same column in late December 1976, with Raid on Entebbe coming out as the better viewing choice.7 Operation Thunderbolt didn’t appear in London cinemas until October 1977, though Robinson judged it “certainly the best” of the three Entebbe films.8 Private Eye offers a mock advertisement for a selection of “New Year Films”—The Entebbe Memorandum, Carry On, Entebbe! Confessions of an Entebbe Pilot.9

Lastly, another well-publicized and contemporary image of the balaclava is attributed to the so-called “Black Panther,” Bradford-born Donald Neilson. Neilson perpetrated a crime spree across West Yorkshire 1971–1974, kidnapping and killing Lesley Whittle, killing three in various Post Office robberies and trying to kill others, and all stemming from myriad house burglaries that grew progressively more violent.

Download

A Book about the Film Monty Python's Life of Brian by Darl Larsen.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31332)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(30934)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30889)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(21283)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18072)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13108)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12931)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(12747)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(12451)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(11883)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(11876)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(8349)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(7834)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(6472)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(6405)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(5768)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(5510)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5036)

We Need to Talk by Celeste Headlee(4868)